Context:

We started our journey towards Karen Barad’s “Meeting the Universe Halfway” by reading Bergson’s “Time and Free Will” (see report here). We then saw Bergson’s initial challenge to psychophysics morphing into the Einstein-Bergson debate about the primacy of physics over philosophy (see report here). We saw that Bergson was not the only one contesting a classical-corpuscular view of mechanistic physics as the ideal for science (and, therefore, philosophy). We discussed A. N. Whitehead’s proposal (see report here) of a more holistic interpretation of the universe based on physico-mathematical interpretations. Although this ‘process philosophy’ was largely ignored in contemporary analytic philosophy, it serves as direct inspiration to a lot of contemporary thinkers outside of that tradition. Our last stop will be dedicated to the philosophical ideas of Niels Bohr explicitly discussed in Karen Barad’s Meeting the Universe Halfway. Bohr also contrasted his ideas explicitly with those of Einstein which made it interesting to look at (the many) alignments and (some) discrepancies of his views, as founding father of quantum physics with the philosophy proposed by Whitehead.

Bohr’s indeterminacy:

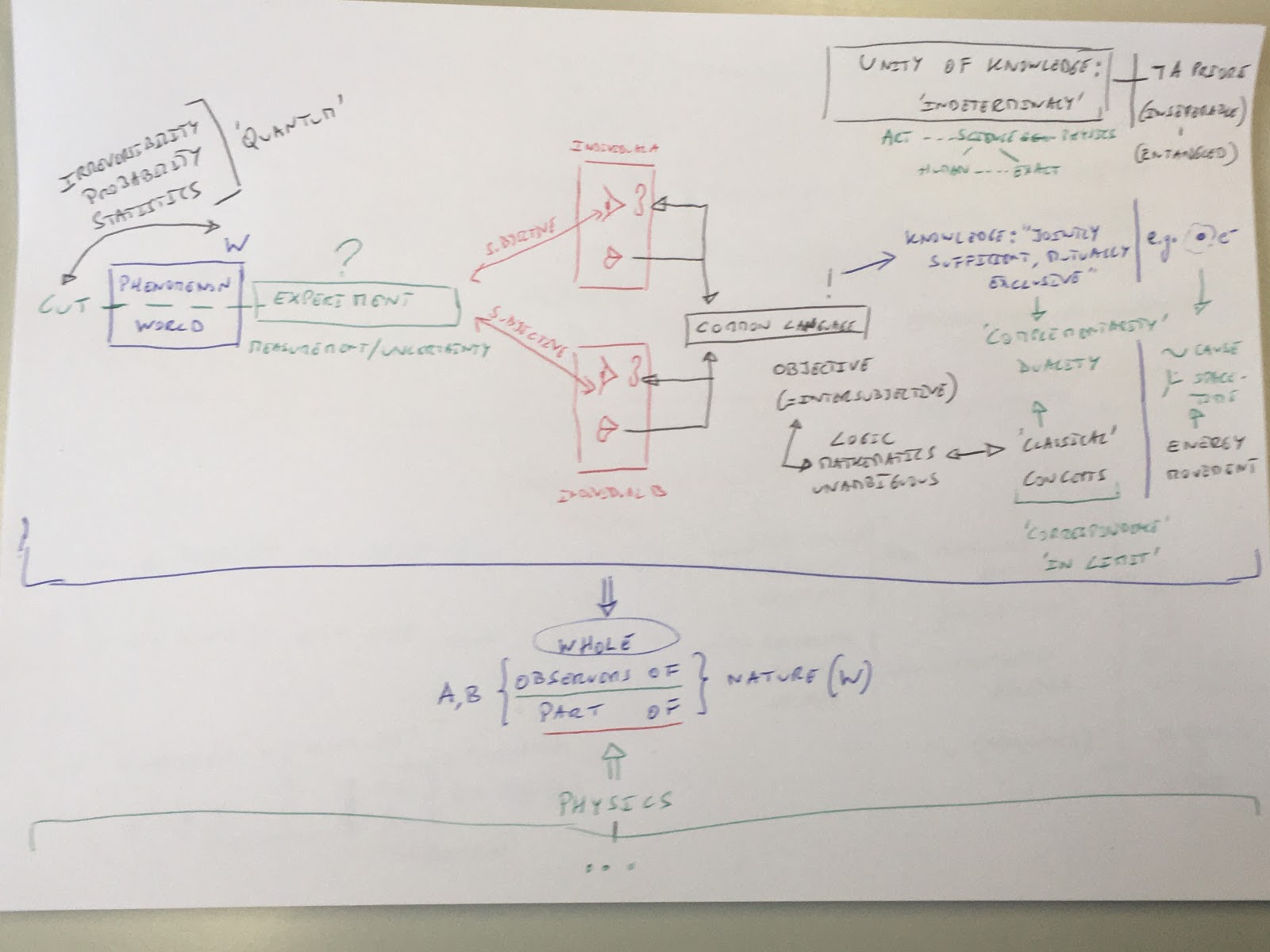

Niels Bohr originated the standard (Copenhagen) interpretation of quantum physics which is highly contested in the philosophy of physics but still stands, well, as current standard. It is an interpretation that Bohr himself defended as an example of a general epistemological lesson across all fields of human knowledge. He did this in multiple papers spanning from the 1920’s up to the 1960s of which we focused on The Unity of Knowledge (1960). This is a paper that avoids most of the mathematical and physical details Bohr leveled against the view of Einstein that quantum physics was incomplete until a more deterministic account is found. Because of that it is probably also a good paper to see that Bohr used the insights of quantum physics as an example of a generic situation across all sciences. He presented indeterminacy as a feature of the unity of knowledge and therefore not as result of the way the universe physically (or ontologically) is. We will briefly explain this with reference to the following picture:

Starting from the red box Bohr’s view clearly was that the way we experience the physical reality is observer-dependent (in fact he argued that Einstein’s relativity theory was already decisive in establishing that). As a ‘philosopher of experiment’ he contended that the only way we can aspire to surpass this observer-subjectivity is by conducting experiments that allow for replication of results by at different scientists (the two central red box). But this is not only a matter of witnessing the same results but, crucially, also a matter of expressing these results in a common language (black elements). The lesson of quantum physics now is that whenever we conduct experiments on atomic processes we find that an experiment asks a specific question related to our ‘classical concepts’ of the world: either we ask for a position (related to a particle aspect of a phenomenon) or we ask for a momentum (related to a wave aspect of a phenomenon). We cannot get full information on both aspects at the same time and, across experiments, we can only find statistical regularities meaning that it is impossible to deterministically predict the result of an experiment of an individual atomic process. Bohr here always links the notions of individuality and wholeness. This may seem strange but, as Dennis Dieks (2019) notes, Bohr’s individuality is linked to indivisibility and therefore also linked to wholeness. Somewhere in our experimentation we introduce a cut (just where is a matter of discussion between us and in the literature, as is indicated in the drawing) in what essentially is somehow entangled with the rest of the world. Bohr doesn’t use the word ‘entangled’ but his constant connection between the quantum and wholeness certainly is related to contemporary uses of that term.

The end result of all this is that in quantum physics, in dealing with phenomena that are of a size close to the Planck’s quantum of action, we find dualities of classical concepts (like particle/wave) that are complementary or jointly sufficient (to explain experimental findings statistically) but mutually exclusive (to describe the outcome of a single experiment into an individual atomic process). This, for Bohr, was an example of something we find across the human and exact sciences (and the arts) or, in other words, indeterminacy is a feature of a unity of all our knowledge. The value of quantum physics is not its originality in this regard but the fact that it established this indeterminacy at the heart of where we looked for a final a priori determinism. In fact, Bohr argued that in this way quantum physics showed that the Kantian a priori’s of space-time and causality were complementary and therefore could not be maintained as a priori truths of the universe.

That Bohr did not see this insight as original – or saw quantum physics as merely a strong example of indeterminacy – is clear from his crediting old Chinese thought with the insight of us as always at the same time being observers (spectators) of nature and being part of (actors in) nature. Those are also complementary aspects that do not allow a full complete disentangling. In the following picture we identify a number of other complementarities that Bohr identified in other scientific disciplines.

Bohr aligned with or opposed to Whitehead?

With this we can come back to the above question with which we ended the last time. As is probably clear from the above, there are more alignments in Bohr’s and Whitehead’s view than there are discrepancies. They both saw the unity of knowledge as lying in a feature of nature that was at odds with determinism and they saw this feature expressed in different ways (contrasts or dualities) across scientific disciplines and artistic expression. They also intimately linked wholeness and individuality and saw continuity of indeterminacy from the (sub)atomic process to creativity in and freedom of expression.

The major difference, one that may prove to be very relevant in reading Barad, surfaced in our discussion with reference to a contrast Bohr draws in his 1960 paper: that between the philistine who takes things as they present themselves and the intellectual who challenges the way we talk about those things. Bohr, in his acceptance of the need to discuss facts in terms of our ‘classical concepts’ limits himself to descriptive metaphysics whilst Whitehead in his speculative approach clearly opts for a revisionist metaphysics. But maybe this is, as well, just a contrast or duality that allows us to make progress without that progress being such to ever be able to achieve a deterministic truth? Still, a remaining difference maybe is the insistence of Bohr on intersubjective language practices and Whitehead’s view on the intrinsic subjectivity of experience which is, as it was with Bergson, somehow ultimate.

References

Niels Bohr, 1960. The Unity of Knowledge. In: Essays 1958=1962 On Atomic Physics & Human Knowledge, 1963 INTERSCIENCE PUBLISHERS a division of JOHN WILEY & SONS New York London.

Dennis Dieks, 2019. Niels Bohr and the Mathematical Formalism. In: Niels Bohr and the Philosophy of Physics, Twenty-First-Century Perspectives (Eds. J. Faye and H. J. Folse), Bloomsbury.